The other day I got an email from a hockey dad that had just downloaded and started diving into Breakaway Hockey Speed, and immediately had some questions. Based on what he told me, he has two sons that have completely different skating styles (which is something I discuss in the manual), and was hoping to get some clarification on “ideal” skating patterns.

He wrote:

Kevin, I signed up for Breakaway Hockey Speed and am reading it now.It’s awesome! It rings very true to me. You don’t look like a very old guy but the observations here would seem to have taken a lot of time or some very careful observation over a number of years.

The reason it rings true to me is that I played hockey all my life and now have two boys ages 12 and 10 who have played since they were old enough to skate. And the two have totally different skating styles.

It’s been a real nature vs. nuture observation for me – they both learned the exact same way and they both did the exact same programs. But they have two very different body types (youngest one lean and flexible, the older more dense with a more limited range of motion) and that certainly seems to have been the biggest difference in their development as hockey players and skaters.

I’ve cut out parts of the message, but his questions and my responses are below:

1) How does one determine their optimal skating depth based on their individual build and joint range of motion (ROM)? Should working on improving ROM be the priority instead of adapting to a sub-optimal situation?

Skating depth based on an individual’s build goes much deeper than muscle flexibility. The contour of the hip joint itself and the length of the femurs relative to the torso will both play a huge role where a player’s optimal body position falls. Longer femurs relative to a shorter torso (this can occur in tall and short people as it’s the ratio, not the absolute lengths that’s important) will necessitate that the player maintains more of a forward torso lean to position his or her center of gravity appropriately above their skates. This will necessitate more hip flexion range of motion, which the individual may or may not have, or will result in a spinal flexion (rounding, particularly of the lower back) which is likely to cause discomfort in this area over time. Allowing this player to skate “higher” than some arbitrary “norm” isn’t allowing them to adapt to a sub-optimal situation, it’s keeping them out of sub-optimal positions altogether. I’m sure these things could all be measured, but that’s really not necessary. You just need to have a good eye for how they move.

In reality, the “ideal” stride is almost the same for everyone: it’s the lowest depth that a player can achieve keeping their hips above their knees, maintaining a neutral spine with their center of gravity balanced appropriately over the skates. In Ultimate Hockey Training, I’ve included some pictures of extreme situations to help illustrate how “lower” is not always better.

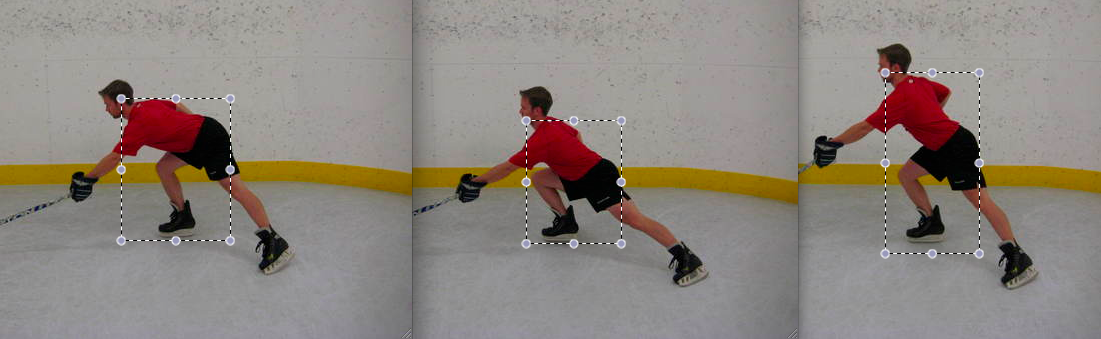

In this picture, the degree of hip flexion (think torso lean) is way too far. Note that I still have a fairly neutral lumbar spine (lower back) in the picture, which is desirable. However, the angle of torso lean is such that it unloads the stride leg, so it’s not possible to produce as much propulsive force off that leg.

In this picture, the degree of knee flexion is way too far. This shifts the COG too far behind the lead leg, but the deep bend also makes roughly the first half of the stride very awkward, as it’s essentially just repositioning behind the COG to be able to create propulsive force.

In contrast to the firs two pictures, this one is characterized by much more mid-range hip and knee flexion angles. This allows a more optimal positioning of the COG over the front skate, while also positioning the body for a strong propulsive stride. In the picture below, I’ve put the three pictures side-by-side, with a box that encompasses the shoulders and the pelvis to provide a crude illustration of where the bodies weight is positioned. Note that the first box is shifted forward, and the second box shifted backward relative to the more optimal stride position.

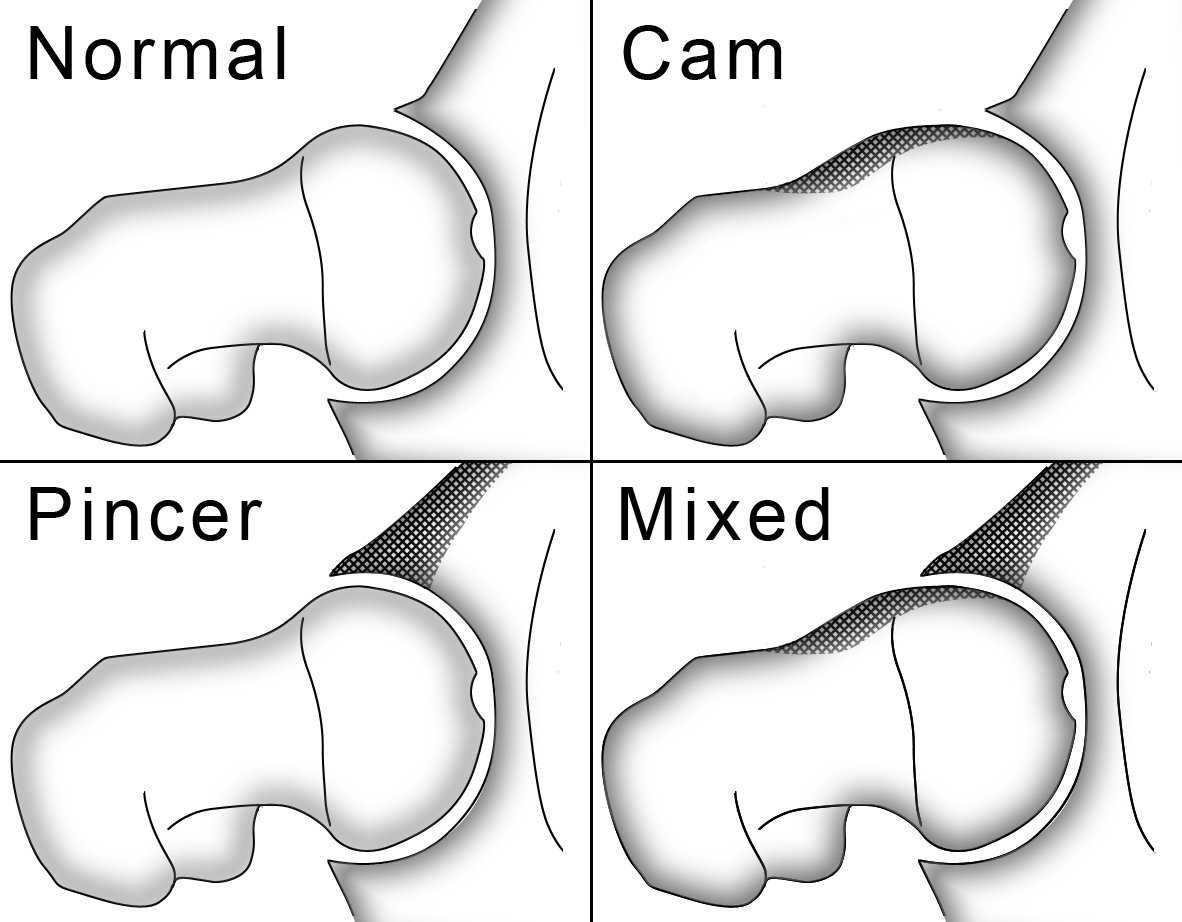

With all of that said, the criterion for an optimal position is relatively similar for most skaters, but the outcome will be much different based on individual structural differences. As I noted above, an individual with longer femurs and a shorter torso may look a little more like the first picture in order to keep their weight positioned appropriately. An individual suffering from femoroacetabular impingement will have limited hip flexion ROM (typically around 90 degrees, compared to 120+) and will therefore need to maintain a slightly higher skating position to minimize stress to their anterior-superior hip labrum (the most common site of tears), and their anterior hip capsule. The point here is that optimal will look different for everyone, and it’s important to identify WHAT exactly may be limiting an individual’s ability to skate at a lower depth (if they appear too high, which is the most common complaint). It could be strength, positional awareness, or structure, all of which are trainable/coachable, but they require very different strategies to address.

2) When you say that most skaters with shorter, choppier strides are “naturally tighter”, what does this mean exactly? Is there any point in working with a skater that fits into this category to attempt to develop the flexibility and ROM necessary to have a closer to ideal knee and hip flexion?

This is an observation I’ve noticed from my time as a player and as a strength and conditioning coach. Stiffer players tend to be faster. This is true in almost all sports. They tend to be higher force output individuals, probably because the stiffness allows them to transfer energy and reduce force better. Stiffness, by definition, means it takes more force to displace the joint through any given range of motion; it doesn’t mean they can’t achieve full ROM. Although this is sometimes the case; the key is to know what they need and ensure that every player has that plus a little “wiggle room”. The idea that more flexibility is better is drastically misguided, and stiffness gets a really bad reputation when it probably shouldn’t.

3) You wrote that about 45-degrees is an optimal stride angle. I’ve noticed that for really effortless looking skaters who have green knee bend and hip flexion it sometimes seems like they are pushing almost straight out to the side at times. I know that just doesn’t sound right and I’m sure there’s no way the mechanics can work but maybe there’s a radius / arcing motion at play that makes it look that way. Just curious if you have ever studied that?

The 45-degree angle is optimal simply because of physics; think Newton’s laws. When an individual pushes through the ice, the stride leg is creating the propulsive force and the glide leg is determining the direction the individual will move, within reason. If a players stands with both skates pointing straight ahead, and pushes straight to the side with the right skate, he/she will either: A) Shave ice with their left skate or B) Fall over. This is despite the “glide leg” being oriented straight ahead. The vector that the individual pushes at will strong bias their movement in that same direction. Just as a push straight to the side would push them straight sideways, a push straight back would push them straight forward. This latter scenario would be ideal, but given the contour of the skating blade, they wouldn’t gain any friction. 45 degrees (or some slight variation of it) maximizes the combination of the forward propulsion vector AND skate blade contact.

That’s a wrap for today. If you haven’t yet downloaded your copy of Breakaway Hockey Speed, you can do so for FREE by entering your name and email in the form below!

To your success,

Kevin Neeld

UltimateHockeyTraining.com

Please enter your first name and email below to sign up for my FREE Athletic Development and Hockey Training Newsletter!