Last week I posted two discussions on the status of youth hockey development that pointed out some commonly held misconceptions, areas that need revamping (or at least have room for improvement) and some of the barriers that the hockey community will face in pursuing a more effective model. If you missed those posts, I highly encourage you to go back and read them before continuing on here today. Check out the links below:

Hockey Development Post 1 –>> The State of Youth Hockey

Hockey Development Post 2 –>> Hockey Development Resistance

Those discussions were primarily inspired by my experiences in learning more about USA Hockey’s American Development Model. If you haven’t yet, I recommend heading over to their site and reading more about it: ADM Kids

Somewhat to my surprise (I thought I’d get more hate mail), both posts were really well received and a few people responded with great comments. One in particular had to do with the apparent discrepancy between the recommendation that youth players participate in multiple sports and activities in order to achieve elite level status later down the road, and the idea that players need to spend a substantial amount of time developing their sport-specific skills in order to perfect their abilities. This latter idea is referred to as the 10,000 hour rule, as some research has shown that it generally takes about 10 years and 10,000 hours of purposeful practice for an individual in ANY field to achieve expert mastery.

It’s easy to interpret the 10,000 hour rule as meaning that hockey players should focus ALL of their athletic time on the game of hockey to accumulate as many “practice hours” as possible at younger ages. Unfortunately, this idea is often misunderstood because “practice” is never adequately defined, and the idea of progressions and age-/developmental stage specificity is often lost. Briefly, I think it’s important to note that taking a young kid and submerging them into a single activity with the intention of making them one of the world’s elite has TREMENDOUSLY negative physical and psychological consequences. For our purposes today, however, I want to focus on what constitutes practice within the 10,000 hour rule paradigm.

In order to understand what counts as practice, we need to have an understanding of what drives performance. At a minimum, it’s important to understand that there are physical and psychological components. The lists below are slight expansions on these ideas.

Physical Components of Performance

Psychological Components of Performance

Again, these lists are far from exhaustive, but are meant to start directing your thoughts as to lesser recognized components of performance and therefore of lesser recognized necessities of practice. So for a young hockey player looking to accumulate as much practice time as possible, what should they do?

10,000 Hours of Hockey Practice

This is a pretty short list, but can be branched out to a wide variety of activities. Structured practice will help players develop technical skills, hockey sense and, at the appropriate age, their tactical awareness. It’s important to recognize that having 100 hours of practice won’t lead to 100 hours of benefit if the players spend the majority of their time standing in lines or staring at the ceiling while the coach draws on the whiteboard. This is one of the strongest points of USA Hockey’s recommendations for players at younger levels and one of the primary benefits of unstructured play-the kids actually get to touch a puck and move around on the ice! Unstructured play will also help develop technical skills and hockey sense, but increases the emphasis on fun (this doesn’t mean not COMPETING, it just means that the competition is for pride instead of the mixed emotions of pride, not letting your coach down, and not getting “Vince Lombardied” by your parents on the ride home from the rink), and ultimately fuels a kid’s passion for the game. Watching game film and next-level hockey will help players develop hockey sense, tactical skills, and components of technical abilities secondary to visualization. In other words, hockey players can improve their performance simply by analytically WATCHING players at the level above theirs.

Playing other sports and off-ice training serve some common and quite supplementary purposes. First, playing other sports exposes kids to different coaching methods, different social groups, different physical stresses, and emphasizes different athletic components. This helps develop highly coachable athletes with lots of friends, that are further from injury threshold and have more advanced athletic capacity. Simply, there is NO wrong here. To provide an athletic ability example (because that’s all the crazy parents and coaches will care about), playing baseball is “hockey-specific training” at younger ages. It teaches rotational power, hand-eye coordination, first step quickness, rapid reaction, and athletic body positions, all things that transfer. Similar arguments could be made for the benefits of soccer, lacrosse, basketball, football, and tennis for hockey. These other sports also provide more opportunities for young athletes to experience success, which is a primary driver in confidence. Also, simply because the “hockey player” is NOT playing hockey, they are maintaining a safe distance from their injury threshold due to overuse/under recovery (e.g. my stress overflow “theory”). Playing competitive hockey year-round is making old men out of young players; the insane number of players we see with chronic hip flexor and adductor (groin) injuries is evidence of a flawed development system. These nagging injuries become career limiting/ending for some, and experience/potential fulfillment limiting in everyone. Referring back to the lists above, it COMPROMISES durability.

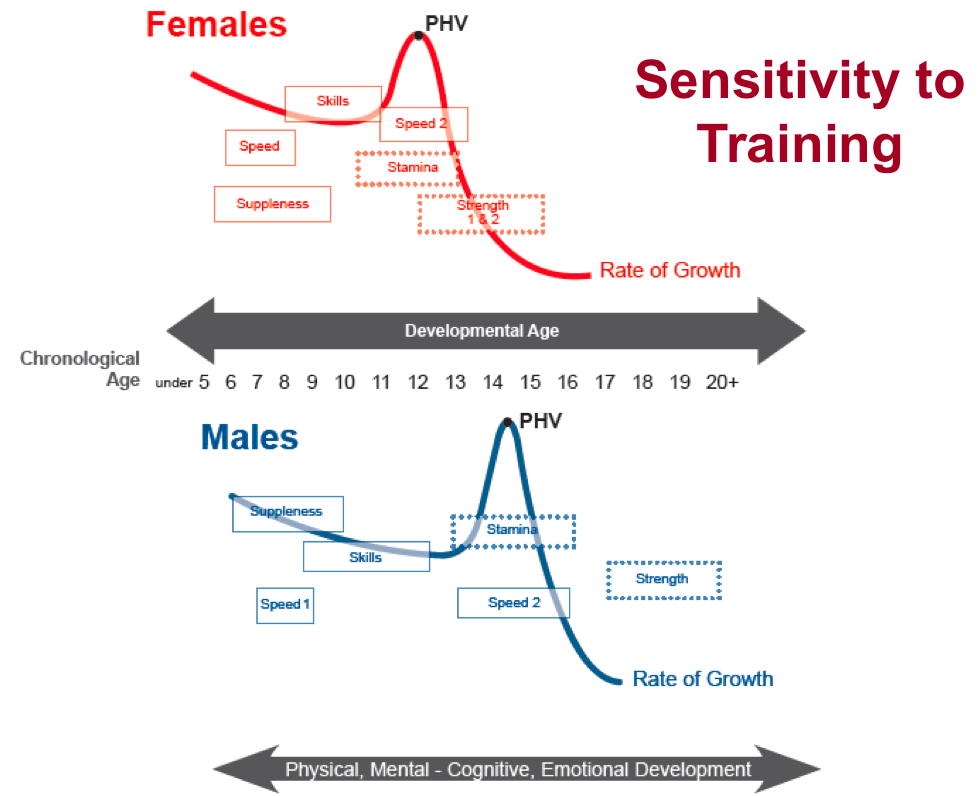

Regarding off-ice training, even BASIC off-ice activities like skipping, hopping, holding single-leg stance, etc. will help improve coordination, rythmicity, balance, and other motor qualities that will positively influence hockey. The nature of the off-ice training should develop in accordance with the physical quality sensitive periods.

Take Home Message

The 10,000 hour rule holds merit in long-term hockey development. If the goal is to achieve elite level status, it’s going to take time and hard work. Throughout this process, it’s important to broaden our horizons on what is considered practice and not ignore age-specific recommendations. 1,000 hours of practice for a 10-year old should NOT look like 1,000 hours of practice for a 20-year old. Seeking to build advanced hockey-specific skill sets on a narrow foundation of proper movement is a recipe for disaster. They call it long-term player development for a reason. Follow age-appropriate recommendations and be patient; excellence is inevitable.

To your success,

Kevin Neeld

P.S. I have a really special announcement later this week so make sure you check back!

P.S.2. If you think other players, parents, coaches, friends, family members, or co-workers would benefit from this information, please pass it along!

Please enter your first name and email below to sign up for my FREE Athletic Development and Hockey Training Newsletter!