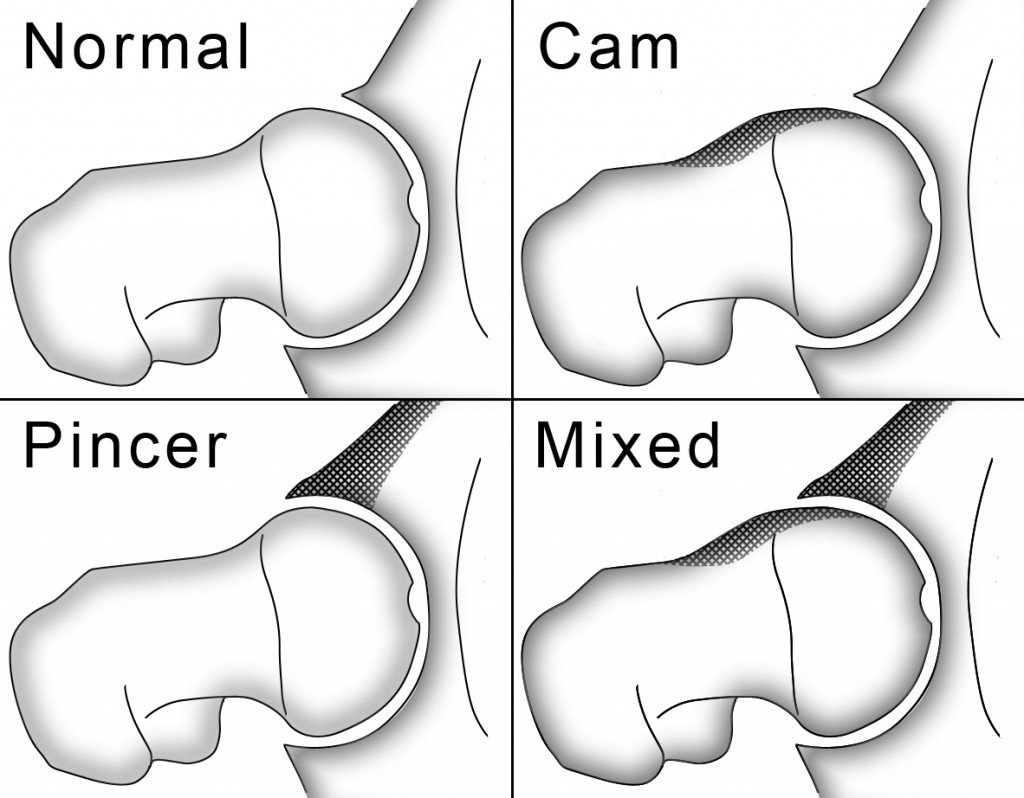

A few weeks back I briefly mentioned that I’ve been working with a lacrosse player with femoroacetabular impingement (FAI). I’ve written quite a bit about FAI in the past, and the posts seem to attract a lot of attention, probably because so many athletes (and especially hockey players) suffer from related symptoms and haven’t had much success in traditional rehabilitation approaches. If you’re new to FAI, I’d highly encourage you to quickly breeze through these previous posts, which discuss a bit about what FAI is, how prevalent it is among hockey player and general populations, and what can be done to train around it:

- Training Around Femoroacetabular Impingement

- Hockey Hip Injuries: FAI

- An Updated Look at Femoroacetabular Impingement

I’ve received several emails requesting to see the video that I posted at Hockey Strength and Conditioning of the lacrosse player with severe FAI, so I decided to throw it on youtube and wanted to share it with you today. Check it out below:

Training Around Femoroacetabular Impingement

This video is of a Division I lacrosse player I’ve worked with over the last several months at Endeavor. He has undergone 4 separate operations (2 on each side) to address his FAI and associated labral damage, and a bilateral athletic pubalgia (sports hernia) repair. He also has significant retroversion, bilaterally, meaning he has plenty of external rotation, but extremely limited internal rotation in both hips. When he first came in, he wasn’t able to jog (let alone sprint), shuffle, or do anything high impact or explosive. In fact, I would say he was generally cautious about movement in general. He’s now in his 6th month of training and can sprint, transition, and move explosively as well as ever. We were able to start moving him toward these types of exercises about 4-6 weeks into the training process. Each week, for the last month, he’s told me that he feels better than ever. I wanted to post this video to demonstrate how important it is to recognize each athlete’s individual limitations. Can you imagine if this athlete was told to squat to full depth, deadlift off the floor, do high box jumps, etc.?

I recognize this athlete’s case is a bit extreme, but the overwhelming majority of the hockey players we work with will be somewhere between this athlete and what is taught as normal. In other words, most players will have some sort of structural deviation that will need to be appreciated in your assessment of their movement quality and exercise technique. In this example, we spent a lot of time early on going through how he would need to move to to stay within his individual confines, but still accomplish what he needs to on the field. After grooving and improving these patterns for several weeks, he now does them without conscious thought, which is the ultimate goal if he’s to be successful.

A few things to look for in the video:

- When he sets up in a quadruped position, his lumbar spine is already in a state of slight flexion secondary to hitting hip flexion end range. Attempting to drive further into hip flexion results in a SIGNIFICANT spinal compensation.

- He can only squat to about 45-50 degrees of hip flexion beefore his lumbar spine begins to flex.

- His hip only flexes about 45-50 degrees during the wall drill, which will have implications for how he runs.

- He is still able to sprint, but he must maintain a more upright posture and de-emphasize his knee drive more than would typically be recommended.

- He has almost no hip internal rotation on either side. The left appears to be slightly better, but this is because his pelvis is not neutral. When I measured this with a goniometer when he first started, he was under 20 degrees on each side.

- Not having internal rotation will have significant implications for rotational movements, which are of paramount importance in most team-based sports (especially ones like lacrosse and hockey). Notice how, when he steps behind during the med ball exercise, he maintains a slight position of external rotation and how he opens up instead of rotating OVER the front leg like most athletes would. Both of these patterns were intentional, and ones that took time to groove.

Another important take home from this video is that this athlete is post surgical and STILL presents with significant range of motion limitations. This is certainly no challenge to the proficiency of the surgeon. In fact, this particular surgeon is regarded as one of the best in the world for this type of work. I’ve worked with several athletes that have had FAI-related surgeries from this surgeon, and some present with “normal” range of motion, and others still have restrictions. It’s likely a result of the complications of the individual case and the risk-reward associated with more invasive or destructive options.

Nonetheless, it’s important for the athlete to understand that getting surgery doesn’t mean you’re going to come out “normal”. It’s likely you will still have significant restrictions that you’ll need to accommodate in your movement lexicon. Also, it’s possible that the FAI is the RESULT of an underlying issue that will still need to be addressed. In other words, in these cases FAI can be thought of as a symptom that provokes other symptoms, none of which are likely to fully subside until the elephant in the room is poached. In some cases, this may mean attacking diaphragm position to restore a more optimal zone of apposition (something I’ll discuss more in the future); in other cases it may require using specific exercises to help restore a more neutral position and orientation of the pelvis; and in others it may simply require strategic soft-tissue work and help restore balance in stiffness across the hips and allow for balanced movement. In most cases, however, a combination of these techniques is warranted.

If you’re interested in more information about FAI, check out the webinar and recent interview I did at Sports Rehab Expert.

Kevin Neeld

P.S. Don’t forget to sign up for Sports Rehab Expert’s 2012 Sports Rehab to Sports Performance Teleseminar! It’s 100% free and features some of the top minds in sports rehab and performance training.

Please enter your first name and email below to sign up for my FREE Athletic Development and Hockey Training Newsletter!

Use CODE: "Neeld15" to save 15%

Use CODE: "Neeld15" to save 15%