Following Monday’s post on Training Around Femoroacetabular Impingement, I got this email from a fellow coach:

Dear Kevin,

I really enjoyed your webinar about assessment and totally agree with most of it. Congrats on your great work.

I have few questions:

1) When you mentioned the Tyler et al study you talked about that maybe skating could change the length-tension curve to the right and said that could be good to work the adductors in shorter length. Can you explain better this concept please?

2) If I understand this well, if an athlete has excessive anterversion or retroversion, it is not good to work end range right?

3) I am excited to know how you program a prevention plan for adductor strains as I read that you reduced these injuries in your athletes over the last couple of years: probably a multifactorial approach right?

Thanks!

First off, I appreciate the kind words and the inquiry for more information. Q&A’s make for great articles because usually a lot of readers/listeners will have the same questions and explanations can help clear things up for everyone. With regards to these questions specifically:

1) As a muscle’s length changes, so does its ability to produce force. Every muscle, and every joint due to the collective influence of all the muscles that cross it will have a point in the ROM where it can produce a peak force.

Length-Tension Curve

As the figure illustrates, during active tension (neurally-driven muscular contraction) the force producing ability of the structure will change in a U-shaped fashion, so that there is an optimal length for maximal force production and a decreased ability to produce force at shorter and longer lengths. This force producing ability coincides with the quantity of overlapping sarcomeres. While this figure, and most of its kind, represent the behavior of an isolated muscle fiber, when tension is represented relative to joint angle, a similar curve presents.

Muscles will adapt to the demands placed on them. Simply, this means that muscles trained in shorter lengths will shift their peak tension toward shorter lengths (to the left on the figure above), whereas muscles trained in longer lengths will shift their peak tension toward longer lengths (to the right). Because the adductors are under maximal tension toward the end of forward skating stride, where they are required to decelerate a high velocity hip extension, abduction, and external rotation at near maximal lengths, I’m suggesting that the high volumes of skating characteristic of most hockey players causes the strength of the adductors to shift to the right, toward longer lengths. As a result, these muscles will test weak if tested in a shortened position.

A great demonstration of a typical forward skating stride position

In the Tyler et al study (The association of hip strength and flexibility with the incidence of adductor muscle strains in professional ice hockey players), they assessed adductor strength in a sidelying position with the hip adducted so that the foot was ~12 inches off the table. They assessed abductor strength with the leg positioned slightly above horizontal. In my opinion, this biases the adductors significantly further to the left on their length-tension curve. This certainly isn’t to discount the results of their study, but I believe their results are more indicative of identifying players who have experienced the shift in peak tension more so than a true strength imbalance. In either case, the training initiative is to restore adductor strength in shortened lengths, a strategy that the same research group demonstrated efficacy with in a follow-up study.

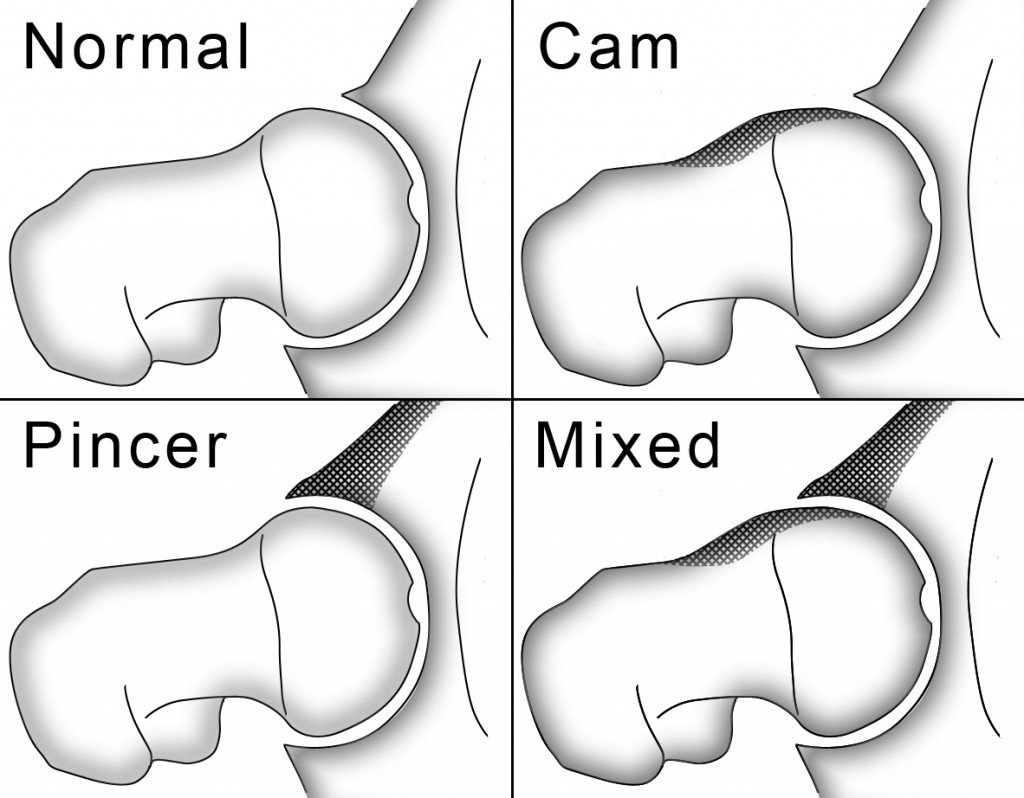

2) Forcefully driving through end range is never good, but that’s not the whole story. When a player hits end range and still needs additional range of motion to complete the movement, they’re going to continue their momentum at another joint, usually an adjacent one. This isn’t a “compensation” per se, it’s just what the body needs to do to achieve the end goal. Knowing whether the athlete has excessive ante- or retroversion will be helpful in ensuring that we avoid forceful end range, but it also gives us a better understanding of what foot positions correspond with a neutral hip position. Typically a slight toe-out position puts the hips in a neutral alignment. If an athlete has severely anteverted hips, a slight toe out could be near end-range hip external rotation for them, which will effect their movement quality, especially in rotation-based movements.

Just as importantly, understanding version angles will provide insight into probable pathological compensations. Continuing with the example of an athlete with severely anteverted hips, pushing backward with their foot at a ~45° angle to skate forward requires a great deal of external rotation of the stride leg, which this athlete will not have. Because external rotation is linked with a tendency for the femoral head to translate anteriorly, it’s reasonable to be suspicious of athletes with excessive anteversion also presenting with anterior hip capsule laxity and/or hip flexor pain/weakness. To use the Postural Restoration Institute’s parlance, we can build in exercises meant to improve the function of “ligamentous muscle”, which simply means using muscles to help reinforce ligamentous integrity/function.

3) The prevention of all injuries requires a multi-factorial approach. Everything we do is leading us closer to or further away from optimal. This is one of the reasons why Charlie Weingroff’s DVD set Training = Rehab, Rehab = Training resonated so much with me. It’s all the same. We’re seeking to improve quality, and then gain capacity by systematically adding quantity. Breakdowns occur with excessive quantity and/or poor quality.

One of the best resources for performance training and rehabilitation professionals ever created

In more specific regards to adductor injuries, we have made a few simple program adaptations for high-risk athletes that has had a profound difference on the incidence and recurrence of these injuries. I don’t think these changes, in isolation, are the solution, but I think they fit into our overall system well to create the response we we’re after. I wrote an article detailing this approach about a year ago for Hockey Strength and Conditioning that you can find here: A New Approach to Handling “Groin” Strains

To your success,

Kevin Neeld

P.S. If you missed the webinar that these questions are in reference to, you can check it out at either (or both) of two of my favorite sites: Strength and Conditioning Webinars, Sports Rehab Expert

Please enter your first name and email below to sign up for my FREE Athletic Development and Hockey Training Newsletter!

Use CODE: "Neeld15" to save 15%

Use CODE: "Neeld15" to save 15%