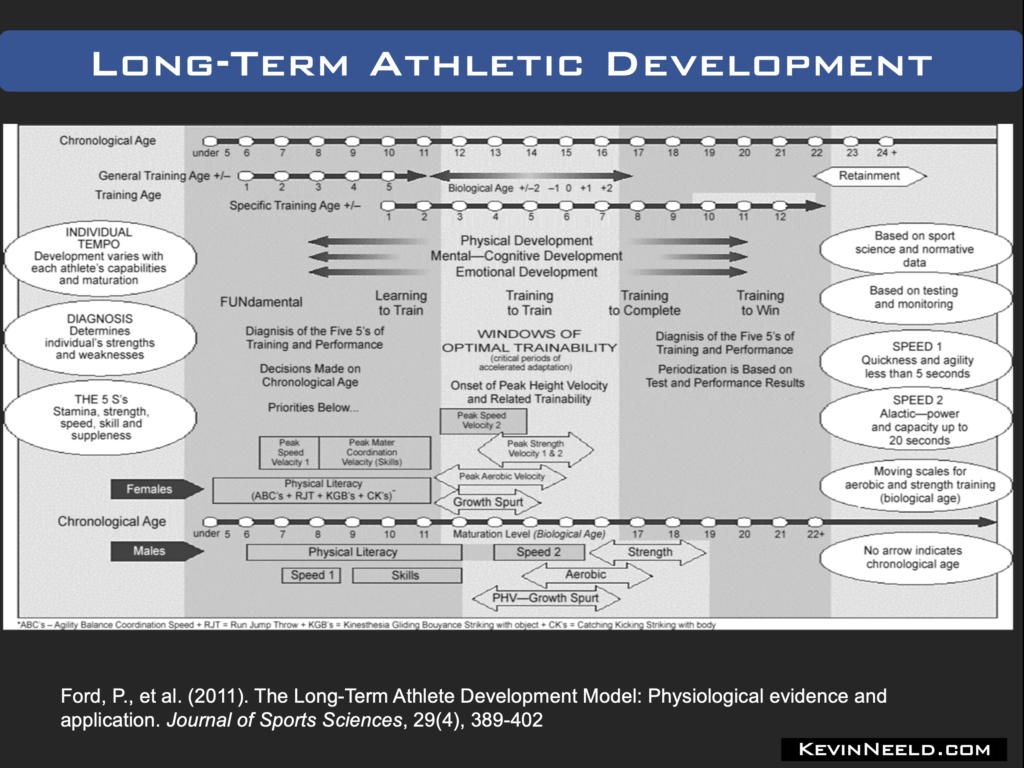

Long-term athletic development models describe themes of training (i.e.,emphasis on fun vs. winning), and phases of accelerated development of specific physical qualities based on stages of development.

This model by Ford et al. (2011), is the most comprehensive I’ve come across, and is particularly valuable because it shows that the stages will be variable dependent on the individual athlete’s gender, biological age, mental/cognitive development, and emotional development (i.e., not all athletes hit the windows of accelerated development at the exact same age).

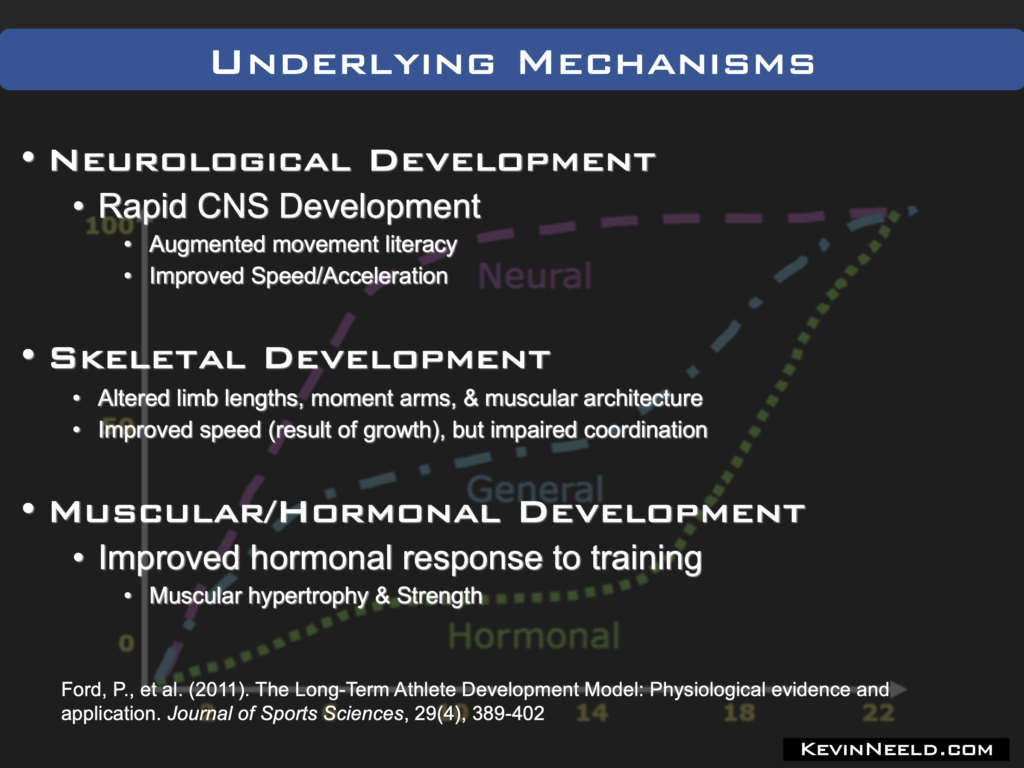

In using this information to influence training youth athletes, it’s helpful to understand the underlying mechanisms that are driving these accelerated stages of development.

For example, the first speed window is improved largely through rapid changes in development of the central nervous system – so in addition to performing short sprints with kids at this stage, it’s an optimal time to integrate a diverse range of movement patterns/skills, NOT just hammer the basics. This is similar to the shift toward teaching foreign languages at young ages.

Acknowledging these stages can help performance and sports coaches design training programs and practices that best facilitate development for their specific athletes, while also recognizing that a HUGE part of long-term development is creating an environment for kids to fall in love with the sport.

Feel free to post any comments/questions below. If you found this helpful, please share/re-post it so others can benefit.

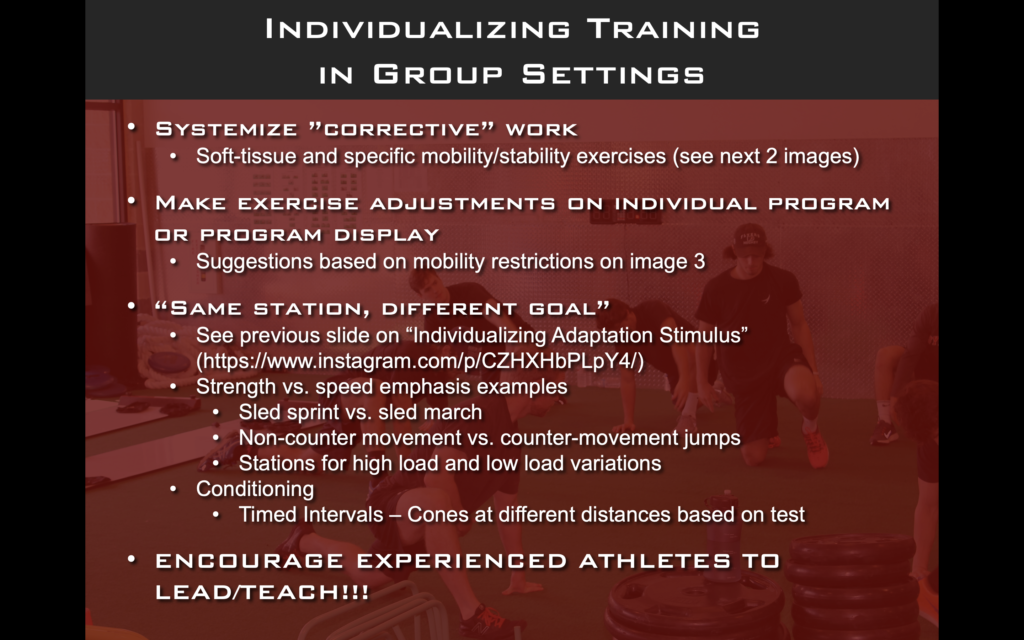

A lot of attention has been paid to long-term athletic development and strategies to develop elite performers. The inarguable truth is… it takes time, and a lot of work.

Unfortunately, this fact has led to aggressive training and athlete development strategies being pushed on athletes at younger and younger ages, which is counter-productive.

Feel free to post any comments/questions below. If you found this helpful, please share/re-post it so others can benefit.

To your success,

Kevin Neeld

SpeedTrainingforHockey.com

HockeyTransformation.com

OptimizingAdaptation.com

P.S. Interested in age-specific year-round hockey training programs? Check out Ultimate Hockey Transformation

Enter your first name and email below to sign up for my FREE Sports Performance and Hockey Training Newsletter!

Use CODE: "Neeld15" to save 15%

Use CODE: "Neeld15" to save 15%