One of the questions we receive most frequently from parents and coaches about our programs at Endeavor is “Is it sport-specific?” Hopefully, based on the discussions from last week, you recognize that there are a lot of things to consider when helping an athlete improve physically for their sport(s). If you missed the preceding posts, you can check them out here:

The interesting thing about the question “Is it sport-specific?” is I don’t think the person asking it really has a firm grasp on what that actually means. Instead, I think there’s this pervasive fear that all athletes will be “trained like football players”, and what they’re really asking is “will this training help better prepare my athlete(s) for their sport?”

As an aside, I think there are worse stereotypes to model on a widescale than football. Football players are known for being among the strongest and most explosive in all sports, they have the longest preparatory off-season, and they have the highest practice:game ratio of all the major sports. If I was going to make a blanket statement, which I understand will be inherently wrong in specific cases, I would say that almost every athlete in every sport would benefit from being stronger, quicker, and more powerful, and from an increased emphasis on preparation and a decreased emphasis on competition.

That notwithstanding, I also don’t know what the parents and coaches asking this question expect to hear as an answer…

“No, we throw a piece of paper for each sport in a hat and randomly draw one to decide what we’ll prepare your athlete for. Hopefully he doesn’t draw polo!”

Using football as an example, consider these questions?

Painted in this light, maybe a better question is “will the training be specific to my athlete’s individual goals and needs?”

The reality is that there are several “layers of individualization” that all need to be kept in perspective when designing a program and making recommendations for a specific athlete. The discussion below will highlight several, and provide some insight into the hierarchy of when to prioritize certain qualities.

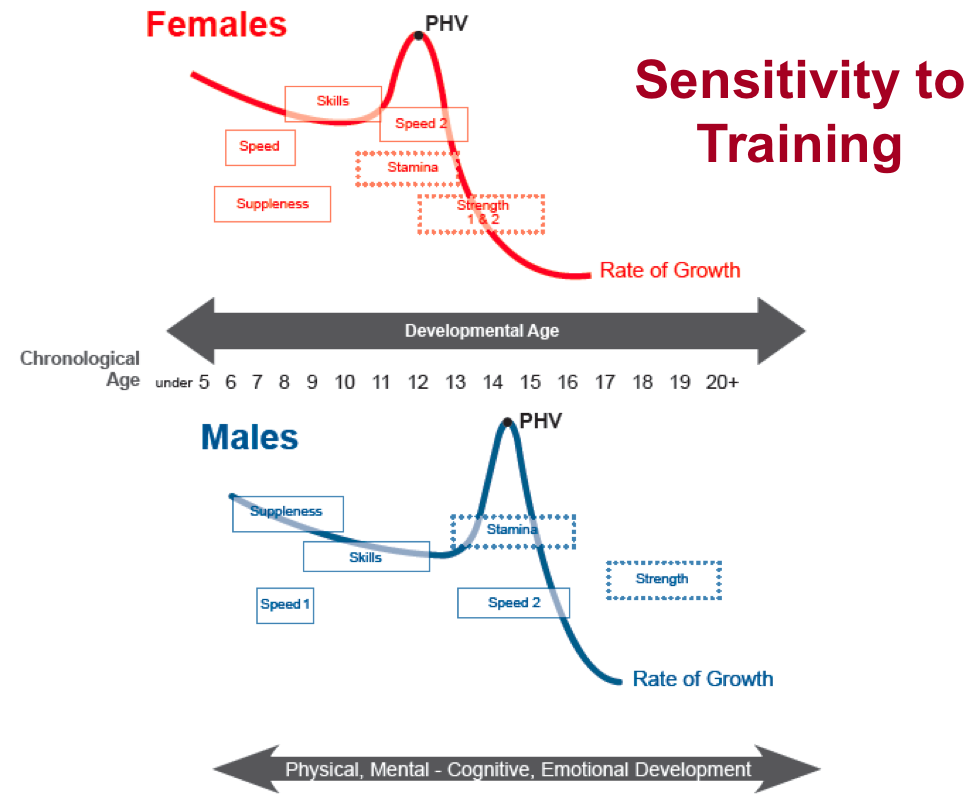

1) LTAD

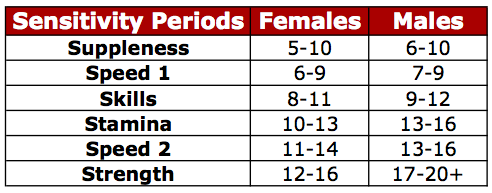

The first layer of individualization is where the athlete is within the long-term athletic development model. Different age groups are associated with the accelerated development of specific athletic qualities, so it’s important to include an emphasis on these qualities while the kids are in this window. Use the below graph from USA Hockey and the accompanying chart I made for a USA Hockey Level 4 Coaching Clinic presentation a few years back to help guide your decision making. The general thought process here should be selecting training methods to directly train the stage-specific target qualities or to train supporting qualities (e.g. sometimes strength is the limiting factor to speed, so strength training can be viewed as strength training).

LTAD Model from USA Hockey’s ADM

Simplified table of sensitive periods for specific qualities at various ages.

2) Gender

Male and female athletes, especially once puberty kicks in, have moderately different needs. While this really depends on the individual (as does everything), female athletes tend to have greater joint laxity, less strength, a greater tolerance for higher volumes of training, and have greater risk of non-contact knee injuries than their male counterparts. There are also differences in coaching methods and motivational sources between genders that need to be accounted for. From a programming standpoint, female athletes may need less flexibility work, more “stability” work, a mildly greater emphasis on strategies to prevent common knee injuries (e.g. ACL tears), and may be able to get away with one more set or 1-2 more reps for each set at any given load percentage. This doesn’t mean that females need an entirely different program, only that slight tweaks may make it more beneficial than using the same strategies for their male counterparts.

This isn’t acceptable for anyone, but we see this type of inward collapse more frequently in female athletes.

3) Sport

Different sports have different movement pattern, neuromuscular drive/force, and energy system requirements that will need to be accounted for in the training process. As a general rule, off-season programs should progress from general to specific in all of these qualities, which will allow for a smooth transition to the pre-season of that sport.

Different training goals for different sports.

4) Position

While many sports share common characteristics among positions, there are also notable differences between some positions within a sport. For example, a football quarterback, kicker, offensive lineman, and cornerback have fairly different needs in terms of their speed, strength, and conditioning. Similarly, a soccer goalie has different needs than a midfielder.

5) Role Within Team

How an athlete is used within a team should influence the way that athlete prepares for the season. For example, if you take a 4th line NHL forward, depending on the team, this guy may play somewhat regular shifts and be used on penalty kills and amass close to 13-15 minutes on average each game. In contrast, another team (or another player on the same team) may only be used sporadically to give the team an energy boost. In the case of the latter, the player would need sufficient conditioning to tolerate the stresses associated with daily practice and travel, and the skill/work capacity to not get killed in a fight (the reality for players in these roles), but would likely benefit from more time spent developing their acceleration, speed, and alactic power. Quite simply, if you’re only on the ice for 15-25s once every 10-15 minutes, you don’t need to have the same conditioning profile as someone playing 30-45s shifts once every 5 minutes. When you play 5 minutes across 3 hours, you’ll probably have a larger impact if you can make a difference with your strength and speed during the 20s you’re out there, opposed to be a little slower, but able to repeat that effort with short rest.

6) Performance Characteristics

Instead of identifying these all separately, it’s fairly intuitive that different athletes will need to have different characteristics regarding acceleration, speed, power, strength, and conditioning to be successful in their sport. This idea is very much encompassed in all of the above ideas. What may not be as obvious, is that all of the above factors can be considered in light of what the athlete currently brings to the table to develop the program that most specifically develops the limiting factor. For example, if the primary limiting factor to be an athlete being more successful is his speed, it’s important to break down speed to the supporting physical qualities: Alignment, mobility, stability, movement pattern efficiency, strength, power/rate of force development. A thorough assessment should identify whether the athlete has an ankle mobility restriction that may be limiting his ability to absorb and transfer force into the ground, he doesn’t run with proper mechanics, his strength is insufficient to support faster running speeds, or he’s strong, but not powerful enough to translate that strength at the required speeds, among others limitations. Once a specific limitation is identified, it’s much easier to target that limitation through specific training.

7) Body Composition

Certain sports and certain positions within sports have certain body composition requirements. I’ve seen very good hockey players be written off as lazy and incompetent because their body fat was 11-12% instead of below the typical standard of 10%. This message has two important lessons: 1) Training programs can be designed to pursue specific body compositions. As a result, training to improve body composition can also be viewed through the lens of how it will improve other qualities (think speed, power, conditioning), not in terms of the training itself, but in terms of how much easier and more efficiently the athlete will move when they’re not carrying around excessive body fat. 2) The perception of an athlete’s work ethic can be tied to their performance strengths/weaknesses (e.g. faster athletes are less likely to be considered lazy in many cases than slower ones), and their body composition. This is interesting because, as with all scenarios, sometimes the athlete with the higher body comp and/or the slower speeds is actually lazy and this stereotype is accurate; sometimes it’s completely off-base and the athlete isn’t one of the fastest and/or leanest because of genetic predispositions. If I’m an athlete, however, I don’t want to give my coach any reason to assume that I’m lazy, which means if I’m not one of the fastest, I would be EXTRA sure to get my body fat below the team standard and make it clear that my performance would not in any way be limited by a lack of effort.

8) Injury History/Predisposition

Training programs can be written to specifically address past injuries to decrease the risk of future injuries. In most cases, this does not need to occur at the expense of other training goals, but simply must be a consideration within a broader program.

Likely to have very different injury predispositions/concerns.

9) Psychological Profile

Simply, the most talented player on the team that is too mentally soft to overcome the “targeting” from opponents and the stress of adverse circumstances common in big games will be of little use to a team. In this context, training that may not fit the physiologically specificity of the sport, but is hard and requires the athlete to dig deep and battle through the challenge may be very appropriate for that individual. Again, I don’t necessarily think this needs to be done at the expense of other training benefits, but I think you can include specific methods within a broader program to provide the athlete with regular opportunities to battle the voice in their head that wants to quit.

Wrapping Up

With all of these factors in mind, there is very clearly more to designing a training program than just considering the needs of a sport. Naturally, it’s not always possible to design the “perfect” program, but I think it’s important to recognize what’s optimal so you can make informed decisions about any compromises you need to make based on logistical factors. As a general rule, I think parents and coaches (and S&C coaches designing programs) should start to think more in terms of “How is this program going to benefit my athlete based on his/her individual needs?” opposed to “Is this sport-specific?” As always, if you have any comments or questions, please post them below!

To your success,

Kevin Neeld

OptimizingMovement.com

UltimateHockeyTraining.com

Please enter your first name and email below to sign up for my FREE Athletic Development and Hockey Training Newsletter!

“…one of the best DVDs I’ve ever watched”

“A must for anyone interested in coaching and performance!”