Hopefully you were able to grab a copy of Eric Cressey’s The High Performance Handbook already and grab all of the great bonuses Eric offered the first day. After reading through the book, I asked Eric if he’d write a post discussing the importance of individualization, which he humbly agreed to. This is a cool post because in addition to discussing individualization, it provides a very simple assessment that provides some valuable information about your structure and how it should impact programming. This is something we see a good amount in baseball players, a little less in hockey players, and A LOT in gymnasts and figured skaters. Check out the article below!

Individualization: How Results Go from Good to Outstanding by Eric Cressey

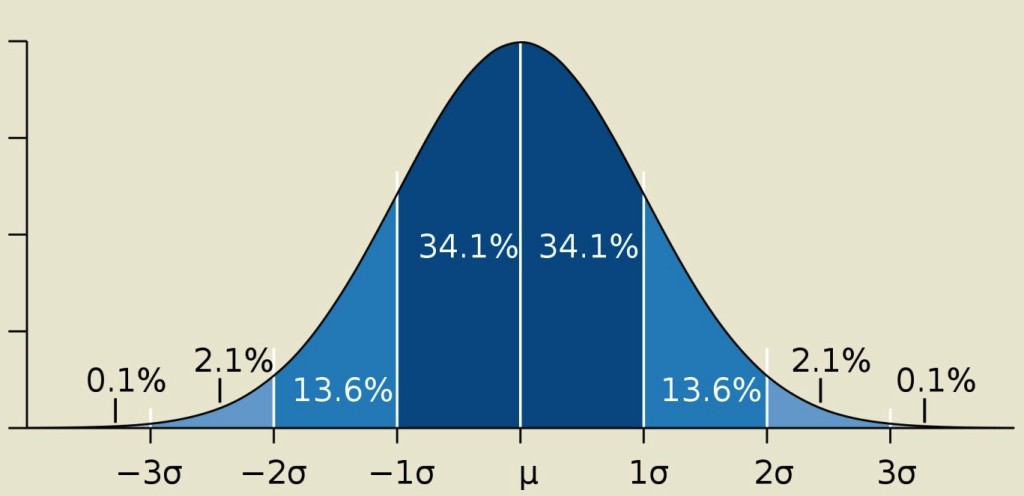

I’m no statistician, but I can say without wavering that the standard bell curve absolutely applies to fitness programs – just as it does to many other aspects of our daily lives. For those of you who need a quick refresher, the standard bell curve represents a normal distribution of data points – meaning values are equally likely to wind up above or below the mean. It looks like this:

The folks in the 13.6% zones (between one and two standard deviations) are a bit more extreme. Maybe they are dissatisfied with the results (below the mean), or really happy with the results (above the mean).

Finally, the remaining 4.2% of people can go in one of two directions. On the bottom side (2-3 standard deviations below the mean) are the 2.1% who wind up royally jacked up. Maybe they start off with structural issues like femoroacetabular impingement (bony overgrowth at the hip) that make squatting incredibly injurious. Maybe they’re beginners who simply aren’t prepared for heavy loading right away. Or, on the other hand, they might be powerlifters who aren’t given sufficient loading to maintain strength. Regardless, they get hurt – or just make absolutely no progress.

The top 2.1% (2-3 standard deviations above the mean) make absurdly good progress and tell all their friends about the program. They’re like the crazy participant in every spin class that sits in the front row and yells, “Give it to me!” at the instructor for the entire hour.

Finally, there is the remaining 0.1%. At the bottom, they’re the ones who’ll badmouth a program to anyone and everyone because their results were so terrible that they can’t wait to rid the Earth of it. Conversely, at the top, there is 1 person in every 1,000 who’ll sing the program’s praises to anyone who’ll listen. It’s his mission in life – because his results were so awesome.

We’d all love to say that all our programs deliver the top 2.2% of experiences, but the truth is, that’s not possible. However, our goal in programming for athletes and clients is to reduce the number of extreme data points on the bottom side. In the process, we shift the entire curve to the right on the client satisfaction continuum – and we keep the lows from being “too low.” It’s a novel concept, but how do we do it?

Very simply, we assess and individualize accordingly.

There are loads of different assessments we can utilize with folks to improve the quality of our programming, but I’ll highlight one here: the Beighton Hypermobility test. This assessment is a means of screening for joint hypermobility. If someone scores high on a Beighton test, then we wouldn’t want to be stretching them – and certainly not to extreme ranges of motion.

The screen consists of five tests (four of which are unilateral), and is scored out of 9:

Now, with that said, individualization often comes at an inconveniences. It’s pricier, more time-consuming, and not necessarily accessible. That’s why I went out of my way to make individualizing a program easier to do when I created my new resource, The High Performance Handbook. Before you start the program, you go through a few quick, but important assessments – and then embark on a program that’s suited to your needs, goals, and schedule.

To your success,

Kevin Neeld

OptimizingMovement.com

UltimateHockeyTraining.com

Please enter your first name and email below to sign up for my FREE Athletic Development and Hockey Training Newsletter!