With hockey seasons at all levels ramping up, I’ve been getting a lot of questions about in-season training. When putting together a program at any time of year, there are a lot of things to consider. Today’s post will dive into the primary considerations when designing an in-season hockey training program.

1) Age of the athlete/Stage of Athletic Development

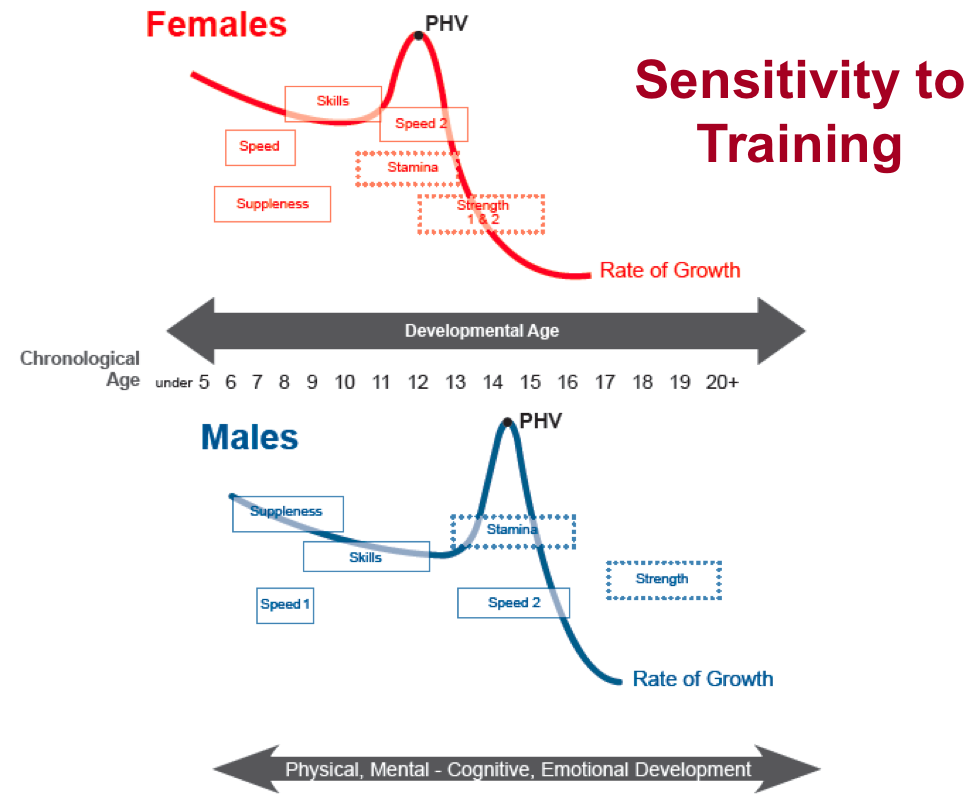

This is a topic I’ve talked a lot about in the past so I’ll just touch on it briefly now. Youth players at different stages of development (largely based on age brackets associated with changes in growth rates) experience windows of time where they’re better able to develop certain athletic qualities. In a comprehensive model, this would influence both on- and off-ice recommendations. This is where USA Hockey’s ADM really excels and provides an outstanding roadmap for on- and off-ice professionals alike to plan their season based on the best long-term interest of the players. The image below is taken from the material and provides a visual illustration of the general ages at which certain athletic qualities are sensitive to accelerated development.

From an off-ice training perspective, I don’t think it’s necessary to ONLY train whatever the quality is that coincides with a given age group. I do, however, think it’s important to keep that quality(ies) in mind while designing the program and consider how the program you’re using is either training that specific quality or supporting qualities. For example, during the “Speed 2” window, it’s not necessary to ONLY do sprints. The reality is that speed can be limited by a number of factors and including things like joint mobility work (despite not being in the “suppleness” or flexibility phase), basic strength work (despite not being in the “strength” phase), and lower body power work will all positively influence the player’s ability to develop speed at that age.

In this context, certain exercises aren’t always what they appear. A kid lifting weights may be “speed training” because it’s teaching him/her to better recruit the muscle mass they do have, even if they haven’t hit puberty and don’t have a hormonal system conducive to putting on muscle mass. I touched more on this topic here: Youth Hockey Training: The Truth About Resistance Training

2) On-Ice Demands

This is a simple concept, but one that I think a lot of programs overlook, at least at the youth levels. Off-season and in-season training programs should be COMPLETELY different in terms of training frequency, total training volume, and training focus/goal because the on-ice demands on the players are completely different (or at least it should be). If we take a step back from being “hockey coaches” or “strength coaches” and just look at all on- and off-ice work in light of the type of stress is places on the body, it’s fairly evident that players at all positions perform dozens of repetitions of short-duration high intensity movements (e.g. speed training) during every practice, and they also experience a multitude of heart rate responses to elicit alactic and lactic conditioning responses. All of these “training” stresses occur during several practices and many also occur during games over the weekend. While different teams across different ages have different practice/game schedules, the bottom line is that there are certain stresses or athletic qualities that are being trained ON the ice that do not need to be further trained OFF the ice. In many ways, hockey-specific in-season training should be anti-hockey-specific.

This is where I think understanding the idea of training complimentary qualities becomes incredibly valuable. How do you improve a player’s speed without doing speed training? How do you improve a player’s ability to perform explosive movements repeatedly with minimal drop-off without doing high intensity interval training? This is where the magic is.

3) Practice Plan/Game Schedule/Travel Demands

To piggyback on the last point, having an understanding of the coach’s practice plan can go a long way in helping ensure the off-ice work is appropriate. Broadly, if a coach intends to bury the players on the ice, it’s probably best to back off from an off-ice training perspective, keeping the volume of the training low and putting a greater emphasis on recovery than on attempting to drive any significant adaptation in speed, power, strength, conditioning, etc. Similarly, if a team just finished a weekend with 3-6 games (especially if they had to travel, which is another stress to the body), and they come in to train the next day (e.g. Monday after a tournament/showcase weekend), the focus of the off-ice training should be in-line with the aforementioned recovery emphasis. If we can agree that a primary goal of training is to reduce injury risk, having an understanding of the total stress load to the athlete is obviously an important piece of the puzzle.

4) Soft-Tissue/Muscle Stresses

This is simply another way of looking at the last two points and comes back to the idea of in-season training being anti-hockey-specific. Hockey players at all levels (incredibly) experience pain/injury to hip flexors and adductors (e.g. the “groin”). These muscle groups have significant on-ice workloads, and even though they’re important for hockey, the time to strengthen/prepare these areas for on-ice work is the off-season. Too much work to these areas in-season is likely to increase injury risk.

I got a question on Twitter last week about when it’s most appropriate to start doing hip mobility work. The reality is that range of motion is much more easily lost than gained, and we (as a society…and DEFINITELY as a sport) spend a significant amount of time “training” our bodies to lose hip mobility by sitting for prolonged periods of time (school, cars, couches, locker room, bench, etc.) and from practicing/playing. A little bit of mobility work on a daily (or near daily) basis is much more effective than a lot every once in a while. Similarly, because we never “shut off” the stimulus to lose hip mobility, there’s never really an appropriate time to stop being proactive to maintain or improve the hip mobility we have.

One of my favorite soft-tissue techniques for the adductors

A mobility/recovery circuit with a lot of quality exercises that can be used in a training program

5) Logistical Considerations

All of the above should contribute to a basic understanding of the goal of an off-ice program for players at different ages and how to make adjustments based on the game schedule. The actual design of a training program will depend on a number of logistical issues, including:

In general, less space, less equipment, more athletes per coach, younger athlete training ages, less social maturity and less coaching experience will all lead to a more basic training program. This doesn’t necessarily mean less effective, just more basic. To dig a little deeper, the foundation of any quality program should be built on optimal exercise technique. If a program requires too much exercise variety (based on the coach:athlete ratio or athlete training age) or exercises that the coach doesn’t feel comfortable teaching, it undermines this principle. The effectiveness of any exercise, in terms of performance benefits or injury risk reduction, is dependent upon the athletes ability to perform it correctly, which is largely dependent on the coach’s ability to teach it. Olympic lifts are great, but if a coach doesn’t have experience teaching them, they probably shouldn’t be in the program. I think all of this is intuitive for strength and conditioning coaches working in a team setting, but it’s easy for a youth hockey coach or parent taking on the added responsibility of off-ice training to read something on the internet (e.g. “the best exercise for speed development”) and come in the next week with exercises they don’t have much experience with.

That’s a wrap for today. If you have any specific questions, feel free to post them in the comments section below! If you want more information on hockey training programs, check out Ultimate Hockey Training!

To your success,

Kevin Neeld

OptimizingMovement.com

UltimateHockeyTraining.com

Please enter your first name and email below to sign up for my FREE Athletic Development and Hockey Training Newsletter!