This seems to be the theme in the introductions of my writing this year, but the last few months have been a whirlwind.

As we were wrapping up another busy Summer, I left for two weeks to work at the pre-season camp for USA Hockey’s Women’s National Team, came home Sunday night, then we had pre-season testing/training Monday-Thursday of the next week for the Philadelphia Flyers Junior Team, and Friday mid-morning I left for my bachelor party weekend in the Poconos.

It was a fun stretch, until I came home to broken water heater and ~20 gallons of water spread throughout our laundry floor and my man cave!

Cleaned up and open for business.

Around the middle of last week I finally got my head above water (pun intended), which brings me to the topic of today’s post.

PRI, CrossFit and Stability

Last Thursday a guy came into Endeavor to get assessed.

He was a former D1 lacrosse player that had transitioned his competitive spirit into CrossFit. He started to transition away from the lifts and into more body weight work after being diagnosed with degenerative disc disease, but was currently experiencing pain/discomfort in his left SI area, lateral hip, left hamstring, and patellar tendon on both sides, but it started and was worse on the left. This was in addition to his low back pain.

When I get emails from people that have pain, especially significant enough that they’ve pursued medical help, the overwhelming majority of the time I refer them out immediately to someone in my network. In this case, the pain was more “sub-clinical” and he specifically requested to go through a “functional assessment” to make sure he wasn’t doing anything that would cause him to get hurt in the future.

The new yearly check-up?

I really admire this attitude. That idea, of periodically getting your movement patterns checked, is something Shirley Sahrmann proposed over a decade ago as an opportunity for physical therapists to pre-emptively help a lot of people by performing yearly movement screens. If you think about it, we do this with our cars (certain things are checked with oils changes every 3,000 miles or so), and it’s common to go see a dentist every 6 months (or so I’m told…I’ve been to a dentist once in the last decade. The Neeld family tree doesn’t possess a lot of super powers, but our teeth are strong), but the importance of optimal movement is completely overlooked by post.

Unilateral pain patterns can have a lot of explanations, but the pattern he’s describing is one I see fairly commonly and can be appropriately addressed using an approach I learned from the Postural Restoration Institute. If you’re unfamiliar with PRI, you can read more about their philosophy, methodology, and education opportunities here: Postural Restoration Institute

The birds-eye view is that the overwhelming majority of human beings have common structural, and more importantly neurological asymmetries that interact with daily movement predispositions to cause predictable movement limitations and potentially pain patterns.

If you’re interested in learning more about PRI, we’re hosting their first ever PRI Integration for Fitness and Movement at Endeavor in Pitman, NJ October 17-18. As of this writing, there are 11 seats still open. I’m particularly excited about the event because there’s an incredible list of attendees already registered, so the discussions will be outstanding.

To be overly simplistic, his lower half was shifted and twisted right; his upper half was twisted left.

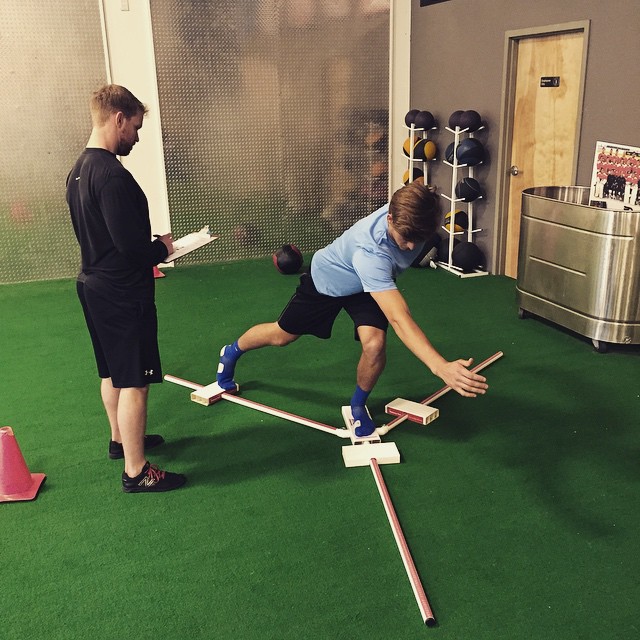

This is a different client, but similar presentation. Note how his pelvis is looking to his right (your left), and how his thorax has counter-rotated back to the left. You can see this by looking at how his sternum lines up relative to his belly button and by seeing how much more stretched his left pec looks compared to his right.

Assessment Findings and Injury Patterns

A few notable findings from his assessment:

- Limited L Adduction

- Limited R Abduction

- Left Hip: External Rotation: 43-degrees; Internal Rotation: 27-degrees (70 total)

- Right Hip: External Rotation: 32-degrees; Internal Rotation: 34-degrees (66 total)

- Seated Thoracic Rotation: Left: ~50-degrees; Right: ~35-degrees

- Active Straight Leg Raise: Left: 1; Right: 3

I also had him perform several movements that he performs commonly in training. I took pictures on his phone (which I unfortunately don’t have access to), but a few things that jumped out right away:

- When squatting down, his hips appeared to be “looking” toward his right knee, not straight

- When pressing a bar overhead, his head was considerably closer to his right arm than his left (e.g. torso was shifted right, but rotated back to the left)

- When he did box jumps, he didn’t load his hips backwards, but dipped straight down (more like a jump shot pattern). He did this during the jump load, the landing on the box, and the landing on the ground when he jumped down.

One of the biggest challenges people have regarding PRI’s contention that all human beings are biased towards certain patterns and consequent limitations is that if everyone has the same limitations and not everyone has pain, then it’s a stretch to suggest that the limitation is causing the pain. There is A LOT that goes into whether the brain interprets something as painful, but from a pure mechanical perspective, it’s important to recognize that whether or not a limitation will result in an injury has a lot to do with the individual’s movement patterns and physical activity.

As an illustration, if your car has an alignment issue such that it pulls to the left, it may not cause any significant issues elsewhere throughout the car (e.g. wearing down one tire, or side of the axel) if you only use it once per week to drive down the road to get groceries. Simply, the demand placed on a subtle asymmetry isn’t enough to cause it to be symptomatic.

Similarly, if you only needed to drive the car in circles to the left, hypothetically, the alignment issue wouldn’t cause as many problems as it would if you only needed to drive circles toward the right. In fact, the alignment issue may make the car more economical in driving exclusively in left circles.

In contrast, if the alignment is off in your 24’ moving truck that you’re using to move across the country, the load of a packed cabin and the volume of movement required to transport from coast to coast will obviously lead to faster breakdowns.

This longwinded analogy is relevant here, because my client started experiencing symptoms while participating in CrossFit, an activity stereotyped by doing trying to do as much work as possible within a finite amount of time. If he played pick-up basketball with his friends once a month, his jumping pattern may have never caused anterior knee pain. But when he needs to, say, perform 100 box jumps as quickly as he can, he’s performing 300 reps (jump load, box landing, jumping off the box landing) in a poor pattern with altered alignment. You can’t always predict what will break down with improper movement, but you can feel pretty confident that SOMETHING will wear down. In this case, all of his discomfort was fairly predictable based on the positions he presented in and how they affected the movement patterns he performed most often.

Quick Fix?

In his case, I decided not to do any manual work. He was already doing some good soft-tissue work on his own with various implements (lacrosse balls, foam rollers, etc.) so I showed him one more that most people haven’t seen before:

[quicktime]http://www.kevinneeld.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Lax-Ball-Posterior-Adductor-on-Box.mp4[/quicktime]

Read more about this here: 3 Rolling Exercises You Should Be Doing

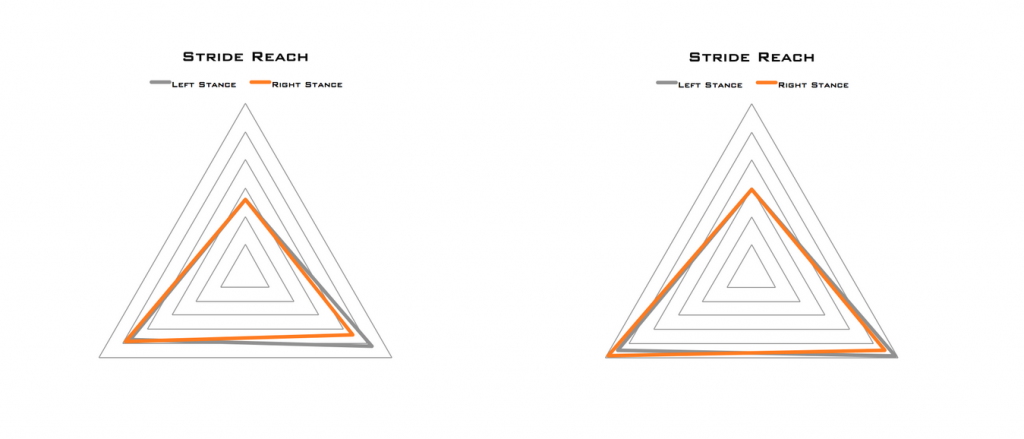

And showed him how to do three exercises that took about 15 minutes to teach and perform: A 90-90 Hip Lift w/ Shift & 2-Arm Reach, a Left Side Lying R Glute Max, and a Paraspinal Release w/ Left Hamstring. The exercises were intended to “untwist” him, and teach his body a few stabilization strategies to hold the new “more neutral” position. When we retested him, he presented with:

- Full symmetrical adduction bilaterally

- Full symmetrical abduction bilaterally

- Left Hip: External Rotation: 40-degrees; Internal Rotation: 32-degrees (72 total)

- Right Hip: External Rotation: 42-degrees; Internal Rotation: 30-degrees (72 total)

- Active Straight Leg Raise: Left: 2; Right: 3

Not only did his hip motion improve, but it became more symmetrical. Of note, his Active Straight Leg Raise was limited, but the 2 was just under the 3 threshold, and the 3 was just over. In other words, they were inconsequentially different, and we improved his left motion by strengthening his left hamstring in a shortened position.

Most importantly, he said he felt better walking out the door AND during his workout later that day.

Naturally, time will tell if these remedial exercises are enough to teach his nervous system how to control his positions and movement more optimally, but the early results are encouraging.

Take Home

High training volumes are sometimes necessary to drive specific adaptations, but if you’re going to perform movements at a high volume you have to OWN them. Layering high volume on top of poor positions or movement patterns will increase the likelihood of a breakdown.

If you’re interested in joining us for PRI’s Integration for Fitness and Movement, you can register here: PRI Integration for Fitness and Movement

To your success,

Kevin Neeld

HockeyTransformation.com

OptimizingMovement.com

UltimateHockeyTraining.com

P.S. If you want to know how to apply this process in a small group or team setting, this is for you: Optimizing Movement

Please enter your first name and email below to sign up for my FREE Athletic Development and Hockey Training Newsletter!

Get Optimizing Movement Now!

“…one of the best DVDs I’ve ever watched”

“A must for anyone interested in coaching and performance!”