A couple days ago, I wrote a long post highlighting three of the major problems in our current youth hockey player development systems. If you missed it, you can check it out here: The State of Youth Hockey

That post was largely inspired by USA Hockey’s American Development Model Symposium, which I attended a couple weekends ago. Today I want to follow up on that post with a discussion on the most prominent barriers that USA Hockey will face in attempting to revamp the youth hockey development programs in our country.

It was interesting to hear speakers with backgrounds in basketball in the U.S., tennis in the U.S., hockey in the U.S., hockey in Canada, hockey in Sweden, and hockey in Finland ALL allude to the idea that parents are one of the largest problems in trying to do the right thing for youth athletes. In other words, it appears that the “parent problem” permeates all sports and all countries.

The Parent Problem Paradox

The idea that parents create an obstacle to doing what is in a kid’s best interest is a bit strange. Why would a parent NOT want the best for their kid? My guess is that not a single parent, not one, would admit that they’re purposely doing something to harm their child’s development. In fact, I would bet that a large proportion of parents would defend their attitudes and behaviors as HELPING their kids, if anything (the rest would probably admit to not really knowing what the best course is and just following the trend around them). In other words, it’s not that parents are consciously out to impair their kids’ development, but simply that there is a disconnect between intention and outcome. The paradox lies in the collective parents’ demands for what they view as best for their kids PREVENTING organizations from implementing what is actually best for their kids.

Of particular interest is where the disconnect originates. In other words, where has the misinformation regarding youth athletic development stemmed from and how has it permeated such a large audience? In this regard, the three largest culprits might be:

- Entrepreneurs

- Tiger Woods

- “This is what I did as an athlete” thinkers

Each of these could be the subject of an entire post, but in brief:

- Entrepreneurs, very wisely, have marketed year-round sports participation as the key to development and exposure. NEITHER of these is remotely accurate, but the people responsible for running “off-season” camps, select teams and tournaments make an incredible amount of money preying on the fears of youth athlete families.

- In April 1997, Tiger Woods won the Master’s at the age of 21, the youngest golfer to ever win. Shortly after, commercials were aired showing a very young Tiger hitting golf balls with his dad. This may have marked the official death of long-term athletic development and the birth of short-term athletic development. On a subconscious level, these commercials set the stage for a push toward early specialization. As Tiger continued to excel, so did the early specialization movement. Unfortunately, the model that produced Tiger is the same model that drives many potential world-class athletes out of sport altogether, and invariably leads to reduced peak performance and injuries in those that decide to stick it out.

- Some ex-athletes simply self-pronounce themselves as experts in that sport. We’ll discuss this more in a bit, but it’s important to recognize how inherently flawed this concept it. First, what works for one person rarely is the best solution for another. Individuals have individual needs. Second, the best coaches are rarely the best athletes. In fact, the more natural certain components of a sport come to a player, the harder it will be for them to relay that quality to another individual or group of athletes. How many hall of fame hockey coaches are there that were also hall of fame hockey players?

To be clear, these factors don’t just influence parents. They also influence coaches, organization heads, etc. In general, the problem in youth athletic development is that the people making the decisions are rarely long-term athletic development experts. It’s interesting, though, that many coaches and parents may view themselves (or at least behave as if they view themselves) as such. When was the last time a parent barged into a dentist’s office and demanded that the dentist did his/her job in accordance with the parent’s wishes. Think that happens to a heart surgeon? A lawyer? An accountant? A skydiving instructor? A street cleaner? No. In almost EVERY profession, outsiders defer to the professional. Athletics, for whatever reason and quite inappropriately, are an exception. Parents know how to coach better than the coach. They know what their kids need. They are the experts. Likewise, coaches with ZERO background or understanding of the physical, social, technical, and social development time courses of athletes are convinced that their system is the best. Does this sound familiar?

It’s interesting that the majority of these people have never heard of Istvan Balyi, the world’s foremost expert on long-term athletic development.

This guy really knows his stuff!

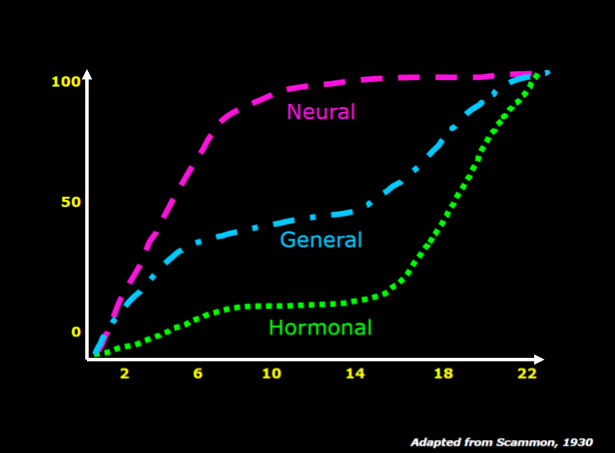

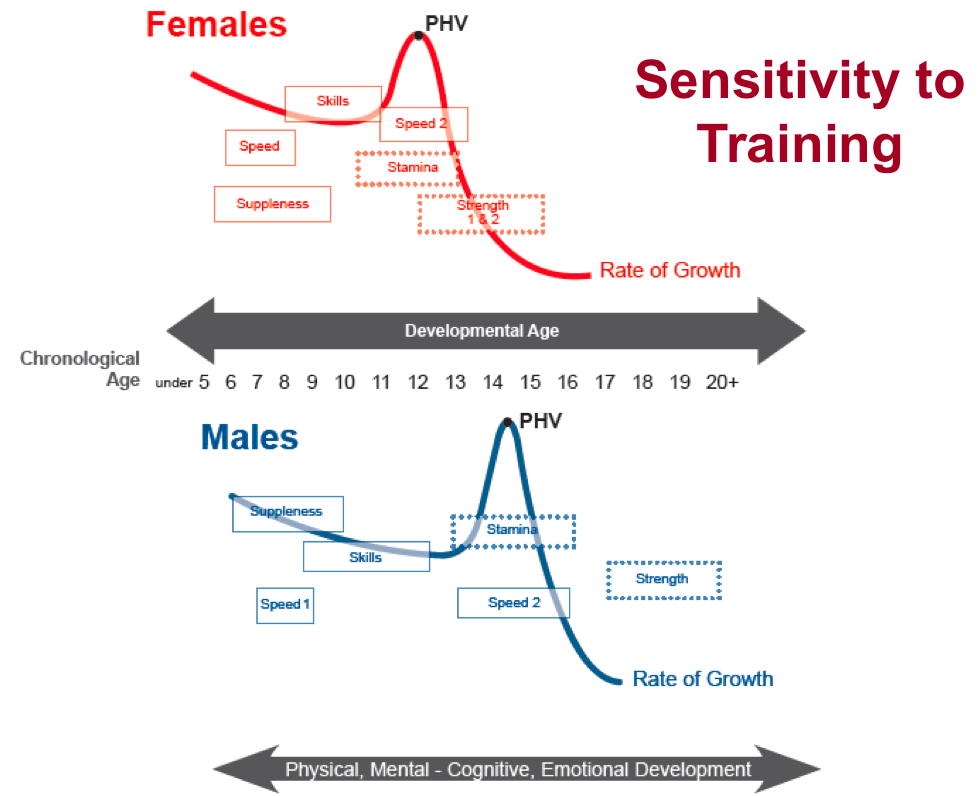

Nor are they familiar with the sensitive periods of specific athletic qualities during a young athlete’s development process.

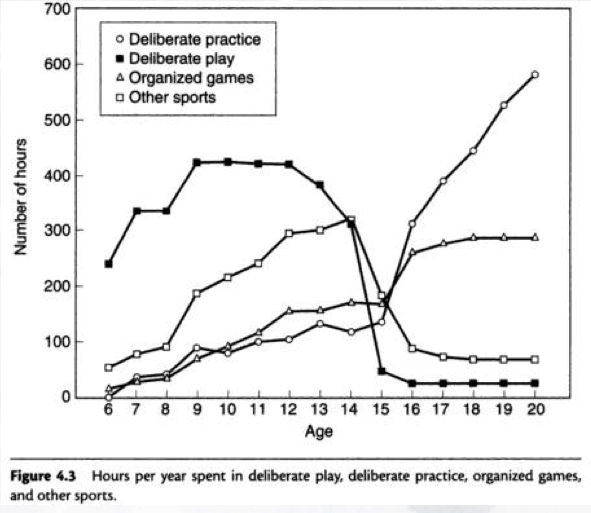

Nor are they aware that research has shown that the world’s best hockey players spend the overwhelming majority of their time during their developmental years playing for fun and playing other sports. Note that deliberate practice (what we think of as normal practice) and organized games don’t take over these players’ sport time until ~15 years old!

Taken from: Soberlak, P. & Cote, J. (2003) The Developmental Activities of Elite Ice Hockey Players. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 15 (1), pages 41 – 49.

I realize that the general tone of this post could be interpreted as blaming parents (and youth coaches for that matter). This is not my intention. In fact, hockey parents and youth coaches are truly heroic in the amount of time and energy they put into helping the kids. I don’t think any sport requires as much of a total commitment as ice hockey (team costs, equipment costs, travel time and costs, etc.). Youth hockey wouldn’t exist without their collective consistent efforts. Instead, the intention of this discussion is one of awareness. Parents are the largest advocates for the development of their kids, but are viewed as one of the larger barriers to positive change.

Ultimately, I think that player development decisions need to be placed back in the hands of the TRUE experts in long-term athletic development (and related fields), and that youth parents and coaches just need to be a little more patient with younger kids. It doesn’t matter if a kid isn’t a superstar at age 10! We shouldn’t be dividing kids by ability at this age anyway. At the mite and squirt levels, kids should have pucks on their sticks for the majority of the time they’re on the ice and should almost never stop moving. It should look like chaos, and it should be fun! By backing off the “rushed development” idea a bit, we can allow kids to develop a true love for the sport, which will be what fuels them to want to put in the time and energy to achieve excellence later in the development process.

I say all that to say this: It will be of great benefit to the hockey community to learn more about USA Hockey’s American Development Model-their intentions, their age-specific recommendations, and their plan of implementation. In a future post, I’ll identify some of the more “big picture” messages that accompany their ADM, but in the meantime you can refer to here for more information: ADM Kids

If your initial reaction to anything you read from their site is dismissive or generally disagreeable, please ask yourself these two questions:

- Do you believe that knowledge has the power to change opinion?

- Do you believe that you possess greater knowledge than the collective group of people that have collaborated in developing the model?

To your success,

Kevin Neeld

Please enter your first name and email below to sign up for my FREE Athletic Development and Hockey Training Newsletter!